Checking Off New Year’s Restorations

Old movies made anew: Perestroika post-punk, Von Stroheim VVinter, Italian Monty Python, and more.

This month I’ve spent a lot of time watching movies at the MoMA thanks to To Save and Project, their annual festival of new restorations. As I wrote in my January movie preview, it’s an oasis amidst the drudgery of Oscars completionism.

Speaking of the Oscars, I got a lot of new readers after Official Substack excerpted the interview I did with my friend Jason about betting on the Academy Awards. I didn’t submit or pay for that, so I don’t really know how it came across their virtual desks.

Jason’s response was “Great. More people to see me miss on my international feature take.” (He put money down on It Was Just an Accident and that is probably not gonna pay off.) We’ll have a follow-up chat in the next couple weeks after he sorts out his second round of bets.

In between catching up on awards contenders, it has been restorative (pun intended) to be part of sold-out audiences for a Russ Meyer sexploitation flick and a century-spanning compilation of independent animation. The series concludes on February 3 and I’ll be at a few screenings this weekend. Here’s a rundown of what I’ve seen so far. I was able to screen one title before its premiere, which I’ve reviewed; next year I’m going to try to do some advance coverage.

The Long Way Home: Remastered and Expanded (1989/2026)

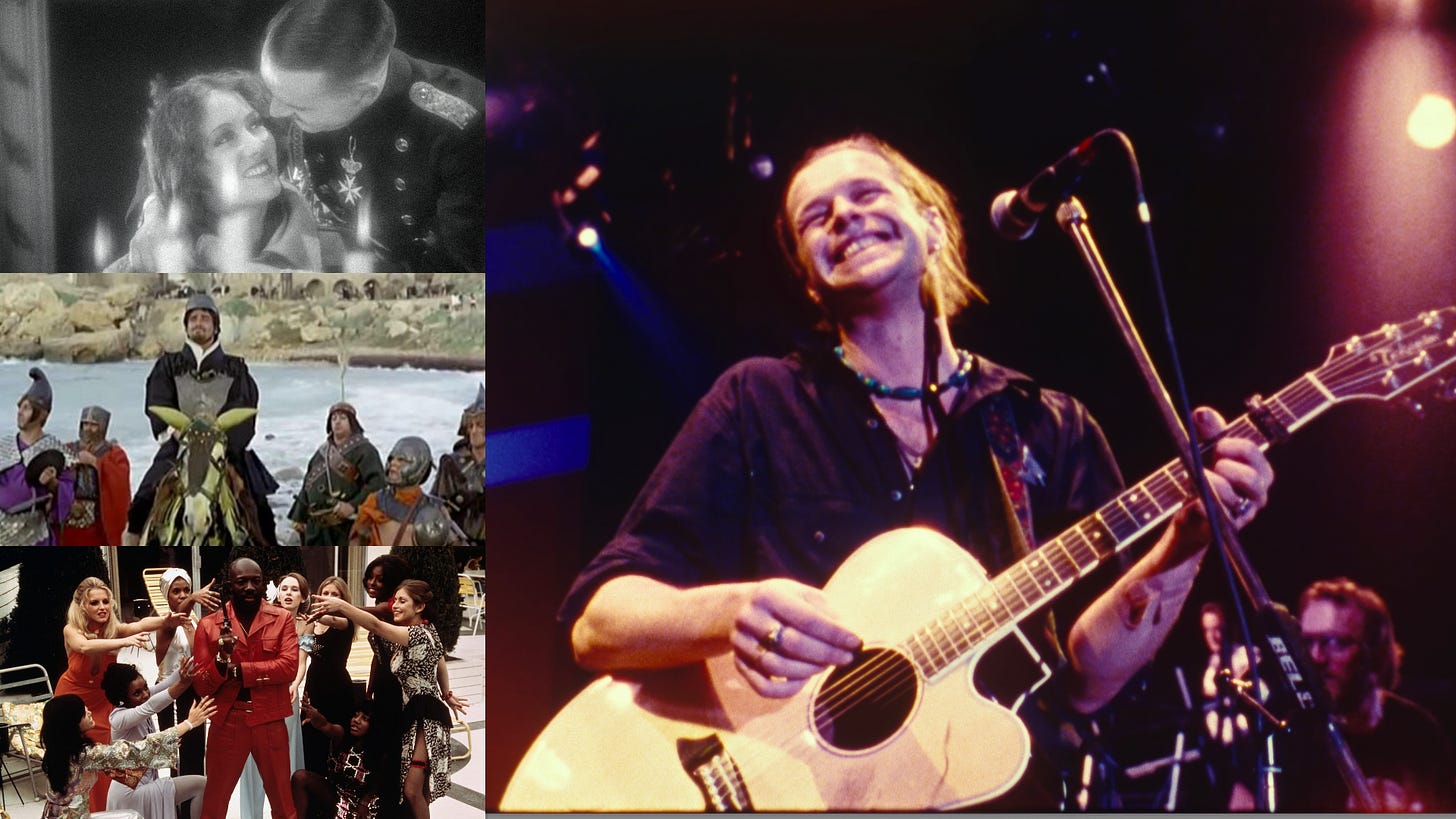

In 1988, at the peak of Perestroika, Soviet rock star Boris Grebenshchikov travelled to America to record Radio Silence, his first English-language album. With hopes of building a cultural bridge between East and West, he brought on Dave Stewart (of Eurythmics fame) to produce and signed a deal with a major label, the first Soviet musician to do so. He seemed poised for a crossover. But Radio Silence would be met with exactly that: the album barely charted in the States and Russian fans felt alienated. As it turns out, crossing over is difficult; for every BTS, there are a hundred Tokio Hotels.

Accompanying Grebenshchikov on this intercontinental journey was filmmaker Michael Apted, best known for the “Up” series and directing a Brosnan Bond. The Long Way Home is a vérité chronicle of a well-intentioned but ultimately ill-fated creative endeavor. Things are going well, at first: record execs are excited about the narrative behind the album, the singer is infectiously giddy as he watches Annie Lennox and Chrissie Hynde lay down backing vocals. But this early optimism gives way to grueling recording sessions across New York, Los Angeles, and London. Something isn’t quite right with the songs but no one can diagnose the exact cause.

The film culminates with a homecoming concert in Leningrad, where Grebenshchikov, playing alongside Stewart, performs his English songs for the first time. Apted captures the mixture of indifference and betrayal across the audience’s faces. It’s not just because they can’t understand his lyrics. The electronic-driven new wave sound of Radio Silence was perhaps too modern and decadent, especially in comparison to the folkier tunes for which Grebenshchikov’s band Aquarium had become famous. During a break in recording, Grebenshchikov decamps to a dacha outside Leningrad. Surrounded by his family and old friends, he gathers his bandmates for an acoustic jam session. Surrounded by acoustic guitars and cellos instead of synthesizers and soundproof foam, he looks far more comfortable than he did in a foreign studio.

The Long Way Home aired on British television in 1989 and premiered at Sundance the following year, but after a VHS release it disappeared from circulation. The original elements had been destroyed. This new remaster is sourced from a 16mm print that producer Steve Lawrence had kept in his basement. Lawrence and Apted had at one point discussed making a sequel, but it never came to fruition before the latter’s passing. To partially fulfill this vision, this re-release includes a new epilogue, which was directed by Lawrence and Susanne Rostock, the original film’s editor.

Almost four decades later, Grebenshchikov’s blonde Legolas locks have thinned and greyed. He reflects on an earlier era of optimism—for himself and for Russia—and discusses how, after the failure of Radio Silence, his love of music was re-invigorated thanks to the “vodka and churches” of his home country. After speaking out against the invasion of Ukraine, Grebenshchikov’s music was banned and he fled to London. The original documentary ends on a note of queasy triumph, but this coda is more hopeful. Despite his struggles, Grebenshchikov remains resilient as both an artist and an activist.

Vibe check:

Original Cast Album: Company (1970) and Stereophonic (a play with music) also put you “in the room” during excruciating recording sessions, though the results are undeniable.

Robert Wilson and the Civil Wars (1985) is another documentary that chronicles thwarted artistic ambition. But at least Grebenshchikov got to make his album: avant-garde theater director Robert Wilson had to cancel his six-part opera tied to the Los Angeles Olympics. (A restoration premiered at NYFF last year; Janus Films has the rights.)

Grebenshchikov emerged from Leninground’s underground music scene. The Russian rock biopic Leto (2018), which premiered in competition at Cannes, would seem to be a fine introduction to this milieu, and a version of him is a character in the film. But Grebenshchikov denounced the movie as “a lie from beginning to end.” So… perhaps not.

Also Saved and Projected

Masters of American Animation, 1914–1998 has an encore screening this Saturday, January 31, and it is not to be missed; Donald Sosin will provide piano accompaniment for the silent shorts.

Oscar winner John Canemaker assembled this excellent survey of New York-based independent animators, which begins with one of his own works, Bridgehampton (1998), a study of the artist’s Long Island garden across the seasons. Made just a few years after Toy Story revolutionized the industry, it now feels like an epitaph to an era of exclusively hand-drawn animation. We then travel back in time to Gertie the Dinosaur (1914), one of the first animated films ever made. Sure, you could watch it on a laptop and enjoy it just fine—that’s what I did several years ago—but it’s certainly more fun to see it on a big screen with live piano underscore.

Also included are vintage Krazy Kat and Betty Boop, Paul Terry’s urban mice (which Walt Disney ripped off for Mickey), and an educational program about rocks with an original soundtrack by Quincy Jones. My favorites of the bunch were Canemaker’s Confessions of a Stardreamer (1978), a whimsical visualization of a young actress expounding about her life, and Hawaiian Birds (1936), a Dave Fleischer cartoon about a disloyal oriole whose husband (?) flies to the big city to get her back. It’s an early example of a 2D/3D hybrid; in some scenes the birds fly across a cityscape model, captured on three-strip Technicolor.

For a complete change of pace, I immediately followed that up with Blaxploitation classic Truck Turner (1974), projected from a newly struck 35mm print. The Museum of Modern Art is an incongruous setting for viewing such a film; they have a strict policy against food and I longed for the musty smell of seats soaked in the popcorn of moviegoers past. Nonetheless, I had a fun time.

I could never predict how mixed the ages would be at these screenings. The animation bill and Truck Turner had a really high proportion of younger folks, but a week later I singlehandedly lowered the mean age by five years1).

Usually I appreciate everything I see at To Save and Project, but this duo of mid-century Italian films were a miss for me. La Finestra sul Luna Park (The Window to Luna Park, 1957) was a fairly unremarkable postwar neorealist drama, though it did feature a strong child performance from Giancarlo Damiani. L’armata Brancaleone (For Love and Gold, 1966) is a medieval parody that predates Monty Python and the Holy Grail by a decade. It was massively successful during its time and the film’s Italian title has since become an idiom for “an ill assorted venture that looks doomed to fail.” Perhaps something is lost in translation because this didn’t do much for me, but this sort of meandering sketch-based comedy is usually not my thing. As they might say in Italy, abbiamo i Monti Pitone a casa.

Queen Kelly (1929)

This is not part of To Save and Project but this new restoration is equally notable! It just wrapped its theatrical run at Film Forum in NY (consequences of getting around to my screener a bit late…) but continues to screen across the country via Kino Lorber.

96 years before Jay Kelly, there was Queen Kelly. Leading lady Gloria Swanson and producer/lover Joseph P. Kennedy (father of John F.) commissioned beleaguered filmmaker Erich von Stroheim to develop an original story and direct it. Though he had made some of the finest silent films in the medium’s nascence, he had cultivated a poor reputation. He clashed with actors and studio execs alike, and throughout his career he was fired on three separate occasions.

Von Stroheim was the first ever auteur terrible, who refused to be constrained by silly things like “budget” and “production schedule.” He’d envision grandiose epics with a runtime to match. His initial cut of Greed (1924) was infamously nine hours long; his compromise was to cut it down to five. The studio wrested the reels from his hands and halved that length. Those original versions are the holy grail of lost films.

Queen Kelly was poised to be just as big. Originally titled The Swamp, von Stroheim conjured a story about a convent orphan (played by Swanson) who becomes the object of desire of a caddish prince. This infatuation sets off a chain of events involving the prince’s jealous bride-to-be (who is the Queen, but not Queen Kelly) that would send the poor orphan to German East Africa. There she would be consigned to a dreadful fate… until her true love finds her. Production went relatively smoothly during the Europe portion of the story, but after shifting to Africa, Swanson began objecting to the content. Her patience thinning and von Stroheim falling behind schedule, the director significantly reduced his screenplay—excising the swamp entirely—but it wasn’t enough. He was fired.

The initial screenplay for Queen Kelly would have resulted in a film five hours long; von Stroheim only managed to complete what was essentially the first act, with portions of the second also shot. Hoping to salvage the film, Swanson devised a new, tragic ending and the Africa plot was entirely excised. This version was still deemed unsatisfactory and it was only released in Europe. Sound film was beginning to dominate and not everyone in Hollywood survived the transition. But it would not be von Stroheim and Swanson’s swan song.

Then came a little movie called Sunset Boulevard, which gave Swanson the greatest comeback any actress could wish for. And Norma Desmond’s obsequious butler was played by none other than Erich von Stroheim. Knowledge of their ill-fated collaboration gives their casting a potent metatextual layer. It’s a bit of a cosmic joke: the once-domineering director now taking orders from his would-be muse. When Joe Gillis and Norma watch one of her old silents together, it’s footage from Queen Kelly that unspools on the projector.

Film restorations tend to be spoken of as purely a technical exercise, no matter how magical they may seem, but sometimes they involve artistic decisions2. In the case of Queen Kelly, the challenge was to bring the film as close as possible to the director’s vision while only using whatever original elements have survived the passage of time. What Dennis Doros and Amy Heller of Milestone Films have made is not so much a restoration but a reconstruction that was the result of extensive research. Filling in the gaps during the Africa scenes are production stills, set design sketches, and newly written intertitles.

And here I’ve fallen into “the fatal temptation,” as Jonathan Rosenbaum calls it, to focus on the extracurricular drama surrounding von Stroheim’s career over his actual work. I just wrote 600 words about a movie without really writing about it3.

The story behind Queen Kelly, both its making and re-making is a great one, but what of the movie itself? Despite the admirable efforts of the restoration team, it still feels like you’re only watching the first third of a story. (I also was not the biggest fan of Eli Denson’s mawkish new score.) As luminous nitrate gives way to fragmented shots and plot summaries that describe what would have been the original ending, I was reminded that, as Norma Desmond declared, “it’s the pictures that got small.”

Despite these insurmountable challenges, I still found myself compelled by this reconstruction of Queen Kelly. Even in truncated form, the sweeping romanticism of von Stroheim’s story nearly overwhelms the senses. I had only known Swanson as the faded diva in Sunset Boulevard, as I suspect is the case for most cinephiles. To see her at the height of her stardom is entirely another experience. With one look, she really could break your heart. It brings to mind another one of Norma’s famous lines: “We didn’t need dialogue, we had faces.” And what faces.

This is not literally true.

Even much more recent movies can be revised during the restoration process, as evidenced by this interview with Gregg Araki about fixing how his film Mysterious Skin would be seen and heard after a botched digital transfer.

For more on von Stroheim’s oeuvre, do read these essays by Richard Brody, for The New Yorker, and Forrest Cardamenis, for his new Substack. Both greatly informed my viewing of Queen Kelly.