Materialists Schemes and Phoenician Cuisines

Freeform thoughts on early summer movies.

It was only in the past couple weeks that I caught up with all the big (to me) movie releases from late May through the middle of June. I was out of town for a few weeks and was then largely consumed with Tribeca. Throughout this I’ve been working on other pieces, for this newsletter and elsewhere. Some are about my recent travels1, others about films; hopefully those will be in publication shape pretty soon. I’m pretty close with a couple of them.

The below movies have already been discoursed to death, but I have thoughts of my own! This is not proper criticism, just loosely written observations. Fair warning I may delve into plot elements, if you care about that sort of thing.

In this edition…

How the fancy restaurants we see in Materialists say more about Pedro Pascal’s character than the script itself (and other ramblings)

What the humble bistro at the end of The Phoenician Scheme may reveal about Wes Anderson

The pulse-pounding Cold War movie that inspired a subplot in Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning

And two things that the Tom Cruise action flick shares with Pixar’s Elio

Materialists

Nearly every movie Substack newsletter that I subscribe to has offered a take on this movie and I’m sorry to add one more.

The A24 marketing team strikes again!! A lot of my friends expressed their disappointment that they did not get the movie that was implied by its trailers. The trailers played into the target demographic’s nostalgia for fun, semi-steamy rom-coms with A-list stars. One even featured a throwback narrator (“In the world of matchmaking…”)

It may go too far to call the campaign deceptive, but it was undeniably successful, with Materialists on track to be A24’s seventh highest grossing film of all time (unadjusted for inflation). But I do find that the marketing unintentionally bolstered one of the movie’s ideas: what we expect when we’re expecting romance. Movie trailers are like Hinge profiles, showing off the best parts and hiding the complications. You can get a sense that you might like it, but it’s only after spending a couple hours with a film (or a person) that you can really know. And like Dakota Johnson’s matchmaking clients2, if you have too many expectations, they will never be fulfilled.

Based on the trailers for Celine Song’s previous movie Past Lives, which I previously wrote “was a canny exercise in obfuscation,” I figured that Materialists wouldn’t really be a romantic comedy, but instead concerned with “the influence of class divisions in romantic partnerships, though who knows if this will be explored in a satisfying manner.” It was not, and judging by the reviews I’ve been reading, I’m not alone in feeling this.

To Song’s credit, Materialists cannily explores how economic anxieties have infected the way we think. These days, everything is judged in relation to its expected value. Never mind how good Sinners is; will it make a profit for Warner Brothers? Sports fans talk more about parlays and over/unders than anything that actually happens on the court; player performances are evaluated vis-à-vis their salaries. Dating is not immune to this stock market mindset, particularly for the types of affluent New Yorkers who populate this film. Lucy’s driving fear, like many of her clients, is in not being properly valued, especially in comparison to everyone else in the relationship market.

(And yet, for a seemingly grounded film about our obsession with money, the numeric details don’t hold up to scrutiny. Lucy comes from a poor family and makes $80,000, but she can afford her own apartment in Brooklyn Heights? This detail, more than anything else, is the most fantastical thing about Materialists.)

The film’s third act undermines the whole. Lucy ultimately chooses love over money, going with Chris Evans’s John (hunky but broke) over Pedro Pascal’s Harry (suave but boring). A thematically consistent approach would have her stay with the rich guy, but Song can’t help but be a romantic fantasist. It would be easier to buy the ending if the characters felt like real humans instead of concepts, and we had a reason to believe that John and Lucy’s bond was so powerful that it overrode her precepts of partnerships. The trouble here is that Song is a playwright first and filmmaker second, particularly in developing her characters. In her venomous review of Materialists, Elissa Suh describes the characters of both this film and Past Lives as “vessels for [their creator’s] lofty ideas crafted exclusively to spout her thesis rather than develop organically as dimensional beings.” Heck, even their names are boring: Lucy, John, Harry.

This newsletter is allegedly about movies AND food

I was curious about the expensive-looking restaurants where Harry takes Lucy during their courtship. The production designer and set decorator have been very open about all the filming locations in Materialists, and their choices ground an otherwise fantastical film. While I recognized Nobu (having recently seen the documentary), I haven’t eaten there, nor at any of the other date spots: Altro Paradiso, L’Abeille, and Sushi Ichimura. But if you follow the New York dining scene in any way, you’re probably aware of them as well, and if you’re not, the striking interiors say enough.

The choice of these restaurants say a lot about Harry as a person. They’re all located in or near Tribeca, where he lives in a $12 million penthouse. For the quietly opulent, nothing is more important than a frictionless lifestyle, which includes how far he’ll go to eat out (in this case, a ten-minute walk that avoids sitting in traffic). They also signify his wealth—taking a girl to a $475 omakase, on a second date, is quite the flex—while signalling a lack of idiosyncratic preferences (otherwise known as taste). You go to these restaurants because it’s the thing you do to impress other people. Ultimately, Lucy breaks up with him because he’s boring.

By the way, the film world equivalent to Nobu is A24. I won’t explain further.

The death of the Big Asian-American Movie?

Here’s an… interesting trend: Asian-American filmmakers break out with a semi-autobiographical story (with a mostly Asian cast) but then their mainstream follow-up largely eschews characters who look like their director:

Lee Isaac Chung (Minari vs. Twisters)

Kogonada (Columbus and After Yang vs. A Big Bold Beautiful Journey)

Lee Sung Jin (Beef Season One vs. Beef Season Two3)

Celine Song continues this dubious tradition. As someone who generally loathes representation politics, I find it admirable that these filmmakers don’t want to be shoehorned as the “Asian storyteller.” I don’t want to lay blame at any one individual. You get the opportunity to work with Oscar Isaac (or, uh, Daisy Edgar-Jones), you take it. They’re bankable stars that will get your movie greenlit. But collectively, it just continues to affirm the idea that Asian actors can’t sell tickets. Greta Lee would have been excellent in this film as the material girl, but we are living in a material world.

On that note, what happened to our Big Asian American movie? Every year after Crazy Rich Asians (2018), we’ve had a film that the Azns would flock to in droves. (A couple years ago it was Past Lives.) It was supposed to be that remake of The Wedding Banquet in April, but it flopped, not getting that same groundswell of boba liberal support. (Too queer in subject matter, perhaps?) To be fair, that film was no cause for celebration. I was going to review it for this newsletter but felt bad, it would not have flattered anyone, especially myself. To Andrew Ahn’s credit, he hasn’t yet made any films about white people.

I haven’t seen anything on the calendar or at the festivals that suggest we’re getting any other films this year that center Asian American perspectives. Woke really is dead!

The Phoenician Scheme

Pleasantly befuddled, as always, by Wes Anderson's mannered expressionism. Not surprised by the mildly divided response to his newest picture. Emotional release is kept safe in a shoebox, and the film lacks the outright catharsis of, say, Asteroid City. Benicio del Toro is excellent as Phoenician schemer Zsa-zsa Korda, whose penchant for intricate designs and tight controls could make him a stand-in for the director himself. Not for nothing that the plot centers around a guy going around to potential financiers to cover a budget shortfall, a universal experience for independent filmmakers.

By the end of the film, Zsa-zsa retires from scheming and opens a humble but bustling neighborhood bistro. In the shabby-chic kitchen, empty bottles of wine are haphazardly piled up in metal bins, which is a bit shocking to see in a Wes Anderson movie. We get glimpses of the food served at Chez Zsa-zsa, as it would be going too far for the director to spotlight anything that wasn’t immaculately plated. From what we do see, it’s more or less typical French bistro fare: boeuf bourguignon, roasted squab, dusty bottles of Montrachet. Perhaps it’s a subtle hint that one day, Anderson wants to retire to a quiet life in Paris, where he currently lives? But there are more schemes to scheme.

I did wonder what would have constituted mid-century Phoenician cuisine. The Phoenicia of the film is very much a fictional country, but the name refers to an ancient civilization on the eastern Mediterranean, largely where Lebanon and Syria are today. The character of Zsa-zsa was inspired by Anderson’s Lebanese father-in-law, so it follows that Phoenician food would more or less be Lebanese. You could make a great dinner menu for this movie: foods of the Levant, soothingly, symmetrically plated like you’d see at a European fine dining restaurant.

Last year, during a trip to Lyon I dined at Ayla, a casual Franco-Libanais restaurant that was a highlight of my trip. I still think about their cuttlefish grilled with beef bone marrow, which had a spicy cumin flavor profile akin to Hunanese food.

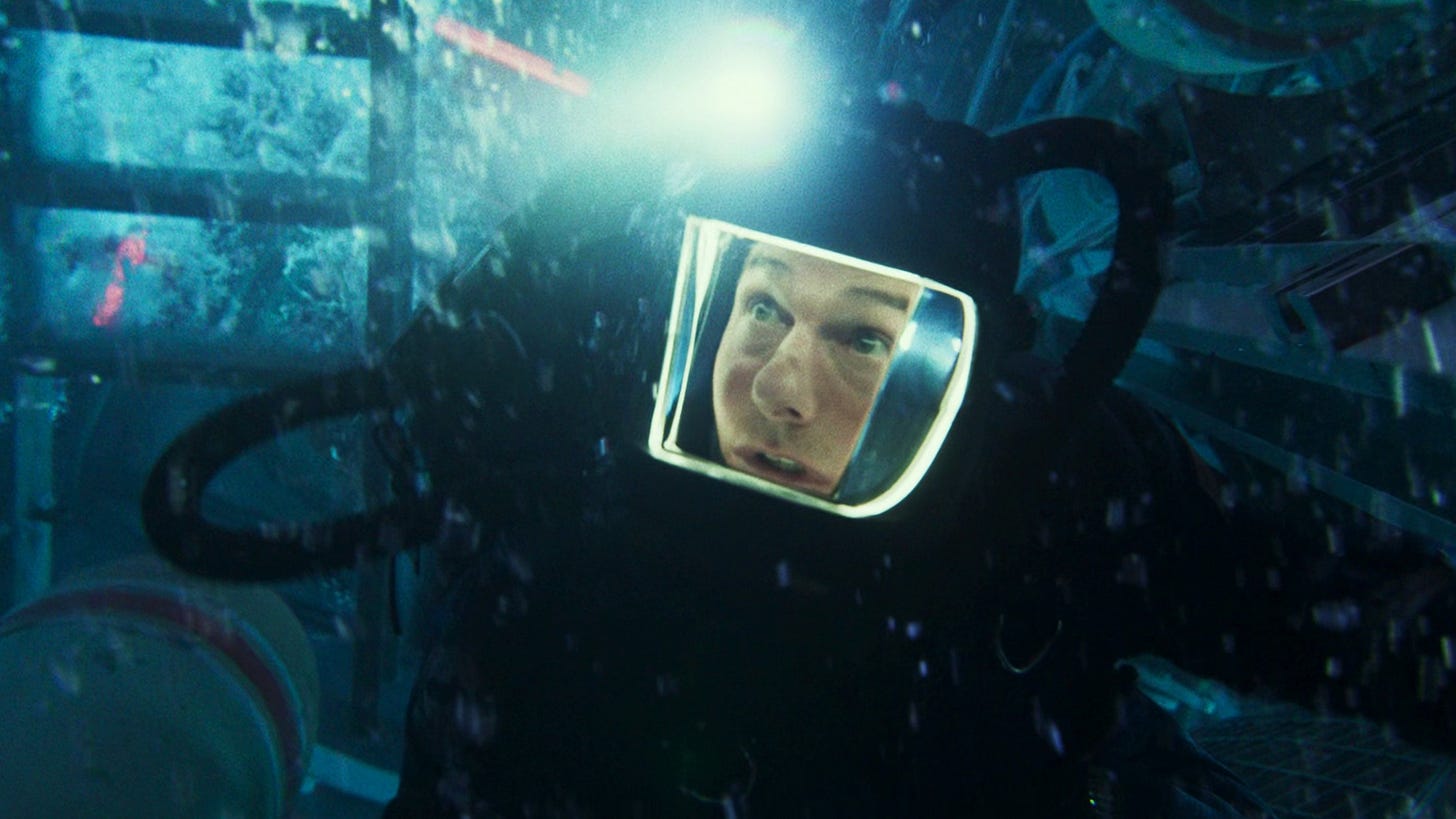

Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning

Ten minutes of this film are visions of a Kamala presidency that never came to be. A neoliberal DEI fever dream where a Black female CIA director becomes the Commander in Chief, with military helicopters piloted by two women and submarines exclusively crewed by muscular gays.

Another ten minutes are spent hanging out with that horny submarine crew in a delightful sequence that feels spliced in from a different (and better) movie. I imagine that the dry, airless sound mix is acoustically accurate, but it only adds to that off-centered feeling. Consider the moment Tom Cruise steps into the sub, and we get a few shots of the sweaty crew striking a pose. Or like all of Tramell Tillman’s line readings. I’m eagerly awaiting that supercut.

The remaining two hours and thirty minutes: everyone telling Tom Cruise he's a God and the only one they trust with the fate of the world. It’s comical how much it happens.

This was easily the weakest of the Missions Impossible, particularly because this is the grand finale. You feel the screenwriters’ unsteady hands as they pivot away from the inert character arcs and plot threads introduced in Dead Reckoning: Part None, resulting in an incoherent story. The repetitive exposition and flashforwards and flashbacks and retcons are a vain effort for some of it to make sense while fitting it neatly within the context of a franchise-ending film. The action centerpieces, as always, are a genuine thrill. But I would have been more impressed if Tom and company had stuck the landing elsewhere.

An excuse to write about Fail Safe, one of my favorite movies of all time

The filmmakers clearly did not anticipate Trump 2.0, because imagine how the Orange Guy would handle a rogue AI taking control of nuclear arsenals around the world. That entire subplot where the President and her brass debate launching pre-emptive strikes is an homage to the Cold War thriller Fail Safe, a perfect movie that everyone should watch.

Released the same year as the better known Dr. Strangelove, the two films share the same premise: the US accidentally launches a preemptive nuclear strike on Moscow and now they have to stop it. Both are cautionary tales about what happens when mankind cedes control to the machines. But they have completely different tonal approaches. Kubrick’s film is one of the best known satires, whereas Fail Safe is stone cold sober.

Both are great movies, but to me Fail Safe elicits a stronger emotional response. Everything is taken seriously but it never feels like a political tract; instead it focuses on the internal turmoil within each character. Unlike Strangelove, everyone in this film is competent and well intentioned, so it's crushing to see them completely powerless to prevent a nuclear Holocaust.

The Presidents of both Fail Safe and The Final Reckoning—played by Henry Fonda and Angela Bassett, respectively—are intelligent, empathetic leaders who place humanity over country. Christopher McQuarrie borrows both the plot and visual style for his little riff on Fail Safe. The camera looks up at the government leaders who have the fate of the world in their hands, and stark shadows that mirror the nature of their thankless work.

Fail Safe was directed by Sidney Lumet, and one can almost draw a straight line between 12 Angry Men, his first movie, and this one. They both feature a small group of men in a room, debating morality and matters of life and death. The stakes have been raised, however, from the life of one person to that of three billion. And that amps up the emotions. Lumet is just so good at capturing faces, accentuating subtle muscle movements when his characters make hard decisions and come to harsh realizations. Those final shots on Henry Fonda are among the most haunting faces ever captured in Hollywood.

Elio

Thematically identical to recent Pixar fare, blending traditionalist messaging with liberal utopian ideals. There's a formula to these plots, but they never fail to make the tears well up. Both human and humankind alike desperately wish that we are not alone, and anyone who felt lonely as a kid will identify with Elio's own feelings of alienation. I share the same thoughts as Dave Poland in that there was a missed opportunity to more explicitly tie Elio's adventures in Alien Land to the grief he feels over the deaths of his parents. In terms of the animation, the DisneyPixar house style hasn't felt fresh in years, but the usage of shallow focus and virtual anamorphic lenses does result in slightly more interesting shot compositions.

Two ways that Elio is like that latest Mission: Impossible film: there's a palpable subtext extolling the virtues of global cooperation and diverse societies, and the final products were radically re-tooled from its initial conceptions. The Hollywood Reporter piece on the erasure of Elio’s queer identity was a depressing read.

Sorry, Baby

Watched this way back in February during virtual Sundance and the theatrical release kicked off last weekend. There was so much hype built around this film, which traces the build-up and yearslong fallout of (to quote the logline) “something bad” that happened to a graduate student, a journey not of healing, necessarily, but of acceptance. But I think that acclaim was a side effect of high altitude festival bubble syndrome: critics and film fans alike are affected by thin mountain air, a lack of sleep, and watching dozens of movies in a very short amount of time. Viewed at sea level, with proper sleep and oxygenation, I didn’t quite see the same movie as everyone up in those Utah mountains. Perhaps I was burnt out too, but on trauma plots.

Unlike most first-time directors, Eva Victor has a clear visual design in their debut feature—wide shots held uncomfortably long, Ozu-like close-ups that place the camera at eye-level with the actor—that complements their patient storytelling. There’s a tenderness in how Victor develops the contours of Agnes’s relationships, whether lifelong friendships or single-conversation encounters, which my friend Jason compared to Kore-eda.

I wouldn't go as far to say that this film is on par with anything from those master directors, though. Victor has spent too much time studying the Greta Gerwig method of acting, which led me to reject this film in the immediate moments after it ended. But it has stood out better in my mind in the months since, perhaps due to strong supporting turns by Naomi Ackie, John Carrol Lynch, and Louis Cancelmi (a hilarious last name given what his character does).

If you subscribe to this newsletter primarily for the non-movie stuff, don’t worry you’ll enjoy the next couple posts.

Her name in the film is Lucy, but let’s be real no one talks about this movie using the names of the characters.

Charles Melton and Youn Yun-Jung are also in the cast, which is different from the prior season, but they appear to play in more supporting roles.