God to Give It Up

Hard to Be a God sounds like a movie invented to mock cinephiles: a three-hour, black and white Russian film with long takes and an inscrutable narrative.

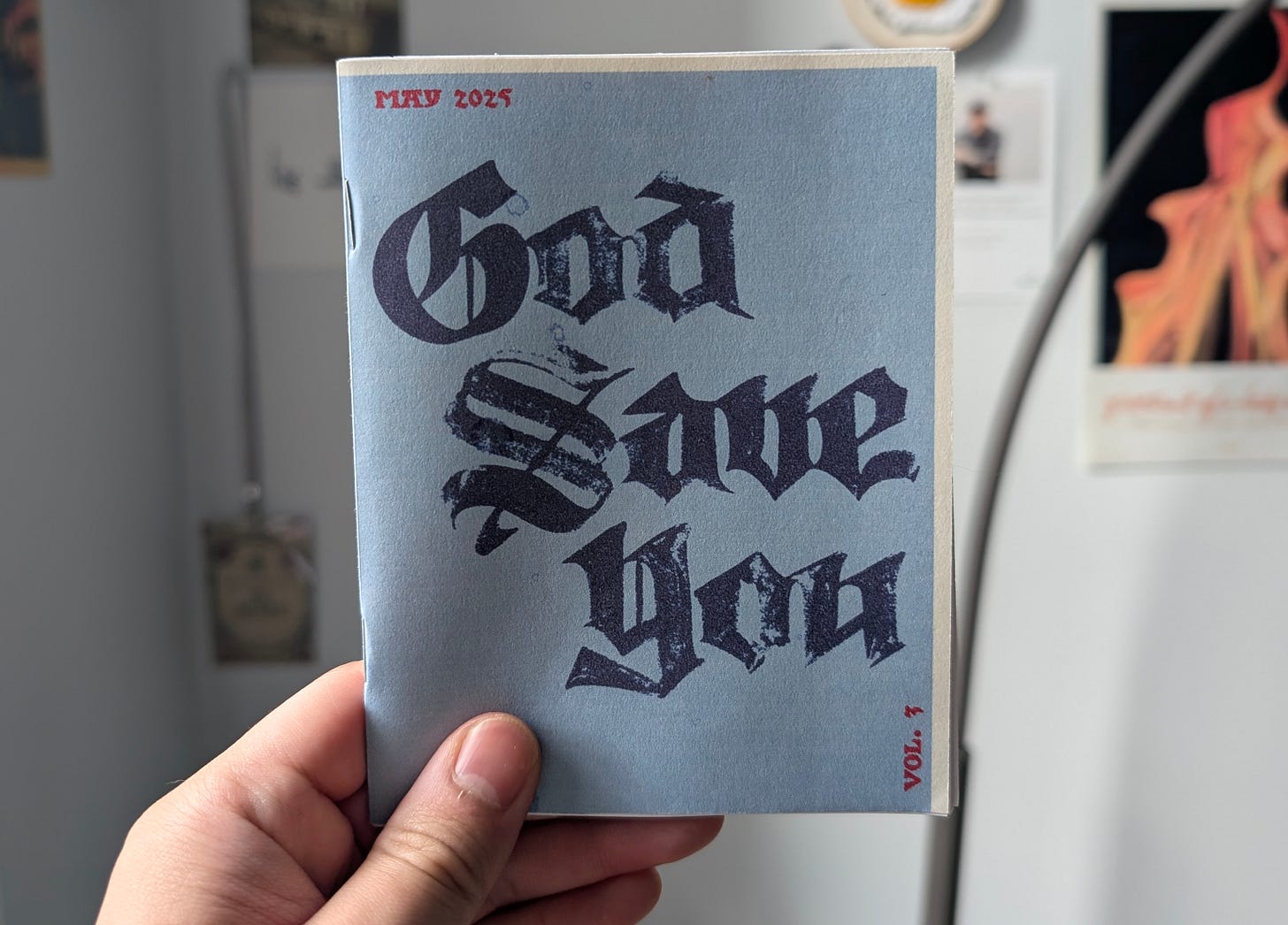

This is my first piece of film criticism to be published in print, in a humble zine created by some friends of mine. If you’ll indulge me, here’s the story of how it happened.

On the second day of this year, Brigid Barber was walking home from the gym when she declared: “It’s Juror January.” Clint Eastwood’s latest film had just been released on HBO Max, and like some of the nation, she was swept up in Juror #2 fever. The bit escalated to the point where she and her roommate Chrissy Griesmer created a zine about courtroom movies, with some of their friends contributing essays and art. Thus was born 4R Press, named after the unit of their Crown Heights apartment.

A Juror January viewing of Witness for the Prosecution garnered an obsession with that picture’s leading lady, which inspired the second issue, “Marlene March.” To keep up with workload, Jake Maher was brought in as an editor alongside Chrissy, while Brigid handled creative direction. Keeping with the alliterations, the third issue was deemed “Medieval May,” and next up is “Shocking Summer.”

I met Chrissy a few months ago as a fellow participant of Reverse Shot’s Emerging Critics Workshop. (I’ll let you know once we have emerged.) When she brought up the zine she had started with her roommate, she was a bit sheepish about it. Distribution was limited to contributors and their friends. Copies were printed, cut, and stapled at home. No one was making any money from this endeavor. It was just an outlet for film writing that was serious but not taken too seriously. But that’s exactly how Reverse Shot began. Now it’s one of the more prestigious outlets of film criticism.

Once I learned about Chrissy’s zine, I jumped at the opportunity to contribute. It took me several days to figure out if I had something unique to say about any movie, let alone one about the Middle Ages. Then I realized that there was one film that eventually set me on the path to becoming the degenerate cinephile I am today, and it happened to be set in a version of the Dark Ages. Thanks to Chrissy and Jake for shaping my messy writing into something sharper and less rambling than this introduction, which was edited by no one. And of course, big thanks to Brigid for having that post-gym thought about a zine that—who knows—may turn into an empire.

After spending the past couple years writing exclusively on the internet, it’s really cool to have a physical object, produced by someone else, that contains something I wrote1, and especially alongside some great essays and artwork. (Printing out my Substack posts just doesn’t hit the same.) One of my goals for the year was to be published somewhere outside of Substack, so mission accomplished. (The other goal was to get paid for writing something. This is still a work in progress2.)

You can follow 4R Press on Instagram for updates, and electronic copies of all three issues are available for you to peruse.

Hard to Be a God

Originally published in 4R Press, Volume 3: Medieval May. Edited by Chrissy Griesmer and Jake Maher.

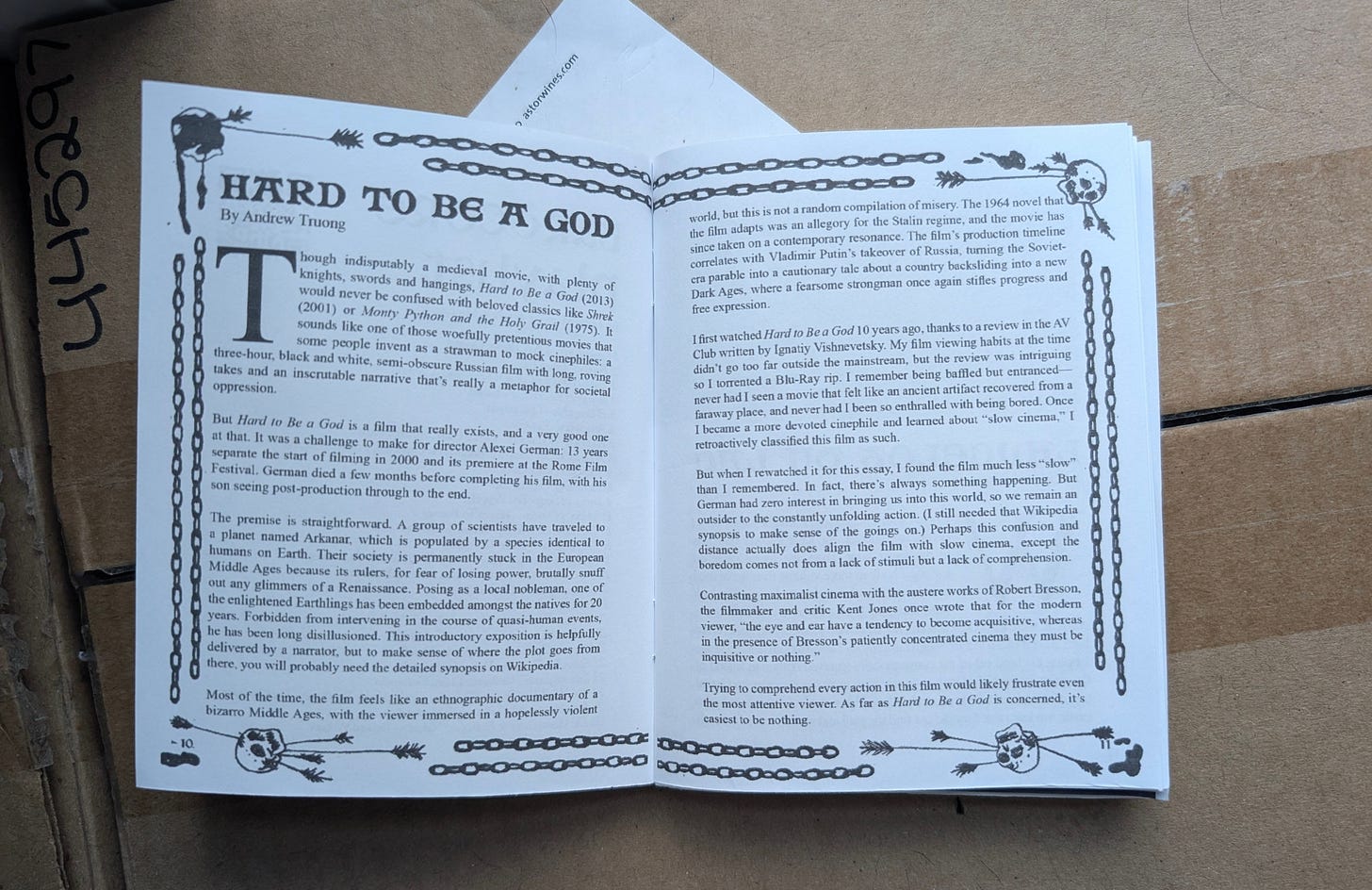

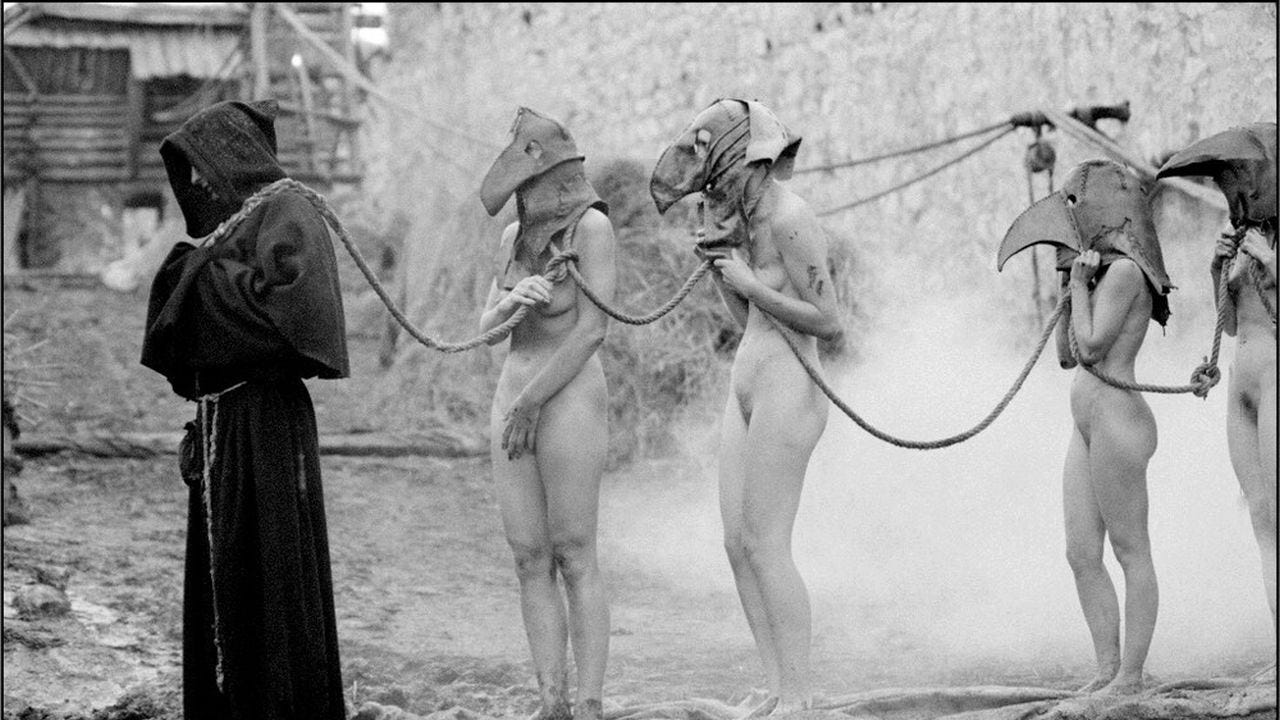

Though indisputably a medieval movie, with plenty of knights, swords, and hangings, Hard to Be a God would never be confused with beloved classics like Shrek or Monty Python. and the Holy Grail. It sounds like one of those woefully pretentious movies that some people invent as a strawman to mock cinephiles: a three-hour, black and white, semi-obscure Russian film with long, roving takes and an inscrutable narrative that’s really a metaphor for societal oppression.

But Hard to Be a God is a film that really exists, and a very good one at that. It was a challenge to make for director Alexei German: thirteen years separate the start of filming in 2000 and its premiere at the Rome Film Festival. German died a few months before completing his film, with his son seeing post-production through to the end.

The premise is straightforward. A group of scientists have traveled to a planet named Arkanar, which is populated by a species identical to humans on Earth. Their society is permanently stuck in the European Middle Ages because its rulers, for fear of losing power, brutally snuff out any glimmers of a Renaissance. Posing as a local nobleman, one of the enlightened Earthlings has been embedded amongst the natives for 20 years. Forbidden from intervening in the course of quasi-human events, he has been long disillusioned. This introductory exposition is helpfully delivered by a narrator, but to make sense of where the plot goes from there, you will probably need the detailed synopsis on Wikipedia.

Most of the time, the film feels like an ethnographic documentary of a bizarro Middle Ages, with the viewer immersed in a hopelessly violent world, but this is not a random compilation of misery. The 1964 novel that the film adapts was an allegory for the Stalin regime, and the movie has since taken on a contemporary resonance. The film’s production timeline correlates with Vladimir Putin’s takeover of Russia, turning the Soviet-era parable into a cautionary tale about a country backsliding into a new Dark Ages, where a fearsome strongman once again stifles progress and free expression.

I first watched Hard to Be a God ten years ago, thanks to a review in the AV Club written by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky. My film viewing habits at the time didn’t go too far outside the mainstream, but the review was intriguing so I torrented a Blu-Ray rip3. I remember being baffled but entranced—never had I seen a movie that felt like an ancient artifact recovered from a faraway place, and never had I been so enthralled with being bored. Once I became a more devoted cinephile and learned about “slow cinema,” I retroactively classified this film as such.

But when I rewatched it for this essay, I found the film much less “slow” than I remembered. In fact, there’s always something happening. But German had zero interest in bringing us into this world, so we remain an outsider to the constantly unfolding action. (I still needed that Wikipedia synopsis to make sense of the goings on.) Perhaps this confusion and distance actually does align the film with slow cinema, except the boredom comes not from a lack of stimuli but a lack of comprehension.

Contrasting maximalist cinema with the austere works of Robert Bresson, the filmmaker and critic Kent Jones once wrote that for the modern viewer, “the eye and ear have a tendency to become acquisitive, whereas in the presence of Bresson’s patiently concentrated cinema they must be inquisitive or nothing.”

Trying to comprehend every action in this film would likely frustrate even the most attentive viewer. As far as Hard to Be a God is concerned, it’s easiest to be nothing.

“Medieval May” is actually the second time I’ve gotten an essay published in a zine, but the first one wasn’t about movies. On the occasion of publishing his new novel, my cousin Kevin produced a one-off zine about what we would miss (or not miss) if the internet disappeared. I put in a few paragraphs about hyper-specific how-to videos on YouTube and a version of the internet that is already gone. The zine was available in certain Brooklyn and Los Angeles bookstores during Kevin’s book events. In keeping with its title, “Offline,” I’ll be keeping my essay exactly that. Though I’ll say it was a trip to see my name listed next to some prominent authors and journalists.

My inbox is open.