Documentaries, Wow

A belated recap of what I saw at DOC NYC, New York's premier documentary festival.

Hi folks! Been awhile. I spent most of December in Japan and have been recovering from jetlag/travel depression ever since. (This was the furthest I’ve ever travelled and the 14 hour time difference is no joke!! I’ll be sharing some food recs/travel reflections next month.)

And welcome to the handful of new readers who seem to be subscribing because Substack suggested you do so when making an account. Whether or not you intended to subscribe, I hope you stick around.

A common theme of this newsletter is that I’m always behind on things, so I’m only just now compiling my year-end lists. Look out for those in the coming days. In the meantime, here’s a belated festival report from DOC NYC. (And yeah, I never closed the loop on those NYFF Dispatches... that final one is coming soon I promise.)

As suggested by its name, DOC NYC is an all-documentary film festival held in New York City. With over 115 features and roughly the same number of short films, the lineup is exhaustingly exhaustive. To make sense of it all, I had enlisted a critic friend to write a report on the state of the doc world, but I’m not sure if/when we’ll be able to get something out there. (She did tell me that most of the films she saw were disappointing, and her fave was WTO/99, an all-archival recounting of an anti-globalist protest and its violent crackdown; my friend Dan interviewed the director for Defector and it looks really good.) So in the meantime, here’s a quick rundown of what I was able to see.

Those just looking to get a head start on Oscars viewing could have looked to the Short List and Winner’s Circle sections; 11 of the 15 films that made it on the Academy’s documentary shortlist were programmed there. It’s nice to see that smaller films like Cutting Through Rocks and Mistress Dispeller (both reviewed previously in this newsletter) are still in contention for an Oscar nomination, though they will have stiff competition from the titles distributed by the likes of Apple and Netflix.

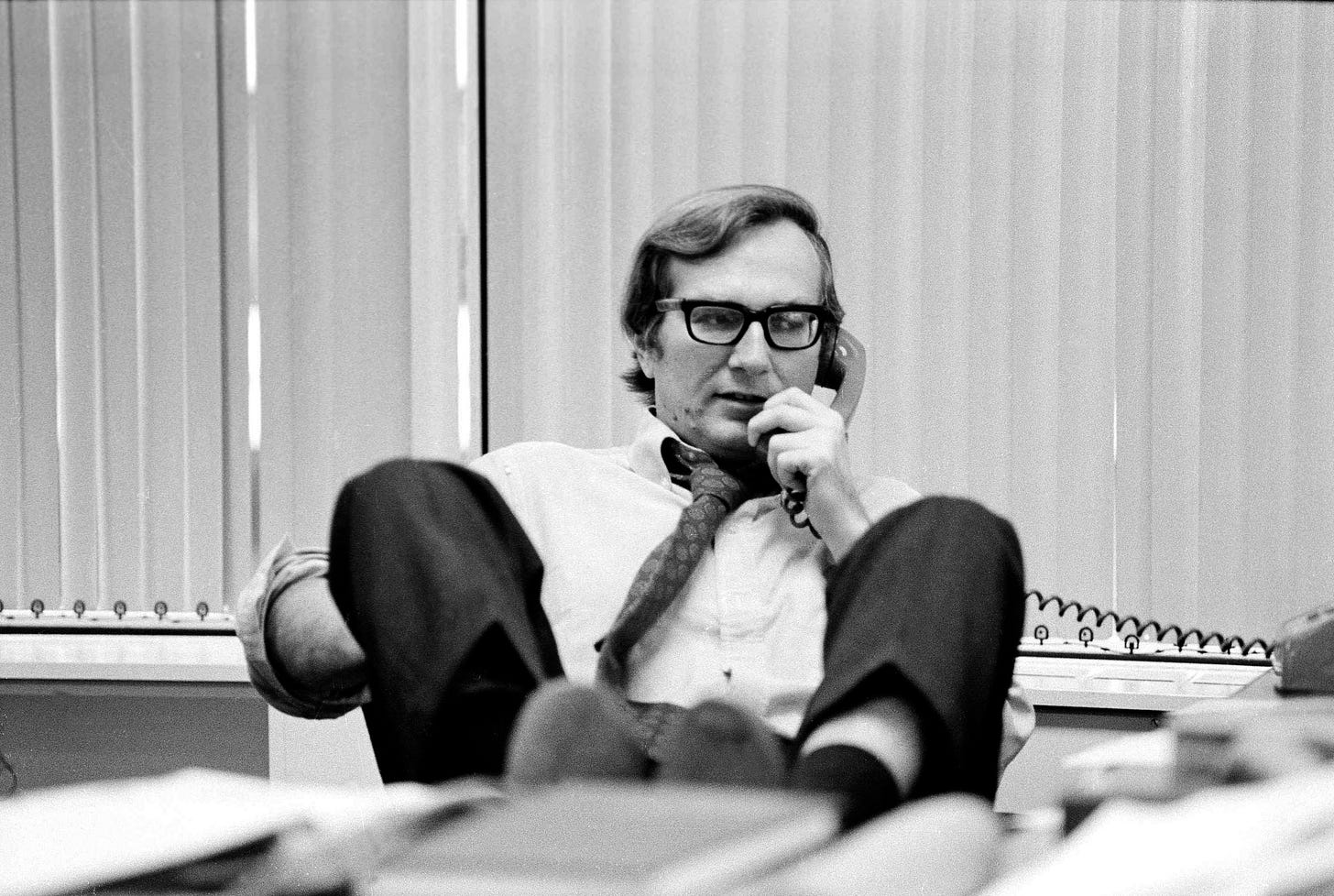

Cover-Up

One such heavyweight is Cover-Up, which is now streaming on Netflix. It’s a profile of legendary investigative reporter Seymour Hersh and the American war crimes that he exposed, from Mỹ Lai to Abu Ghraib and beyond. It is surprisingly entertaining. Despite (or because of) his profession, Hersh has that prickly and witty New Yawk charm; he knows how to spin a yarn. Directors Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus were smart to take a non-chronological approach, intuitively collapsing a half-century of history into a time loop of dehumanization wrought by America’s military and intelligence agencies. But when it comes to Hersh’s late career missteps—al-Assad apologetics, an overreliance on single sources—the filmmakers pull their punches. Hersh once worked at the New York Times, where his work was scrutinized by editors and lawyers; now he’s unfiltered on Substack. That can be attributed to his irascible nature (which does come out in full display in the film), but it also tracks with the decline of investigative journalism and traditional media writ large.

Predators

A similar throughline can be found in Predators, a surprisingly personal interrogation of To Catch a Predator and its troubled legacy. It was irresistible television: vigilantes would pose as teenagers in online chat rooms and arrange for an IRL meet-up with pedo pervs. The men (they were always men) would show up to a house only to find a camera crew and a squad of cops. Chris Hansen, the program’s host, inspired countless memes and parodies. The wildly popular series came to an ignominious halt when a prospective target killed himself just off-camera. Seventeen years later, an unrepentant Hansen has shifted from NBC to YouTube, taking part in a creator economy that even more cravenly chases views. Predators didn’t make the Oscars shortlist1 but that doesn’t make it any less worth watching. Ultimately it does what the Dateline NBC show (and its mutant progeny) never could: help us understand.

The Gas Station Attendant

Outside of potential awards contenders, worthy films were found in the rest of the DOC NYC lineup. Karla Murthy, a longtime producer for PBS News, turns the proverbial lens around in The Gas Station Attendant. The titular attendant is her father, a striving Indian immigrant who briefly moonlighted as one—literally so, he worked the nightshift—in between a string of entrepreneurial ventures. Midnight phone conversations between Murthy and her father during this stint, along with a trove of home movies, are the backbone of the film. (There is also some fantastic file footage throughout, put together by archival producer Peter Nauffts.)

This particular strain of first-person documentary, in which a second-gen immigrant recounts their parent’s travails while navigating their flawed relationship, has become an overly familiar narrative, at least for this second-gen immigrant. (After all, per a saying in the father’s native Kannada, “everybody’s dosas have holes in them.”) But this particular telling is an engaging one, and through her journal-like narration Murthy reveals the film was made not for herself, but for her own children to keep alive their immigrant roots. Not even I was immune to feeling a well of emotion, for both Murthy’s family and my own. And I’ll never dislike a film that features a passionate karaoke singalong to an Avril Lavigne power ballad.

Y Vân: The Lost Sounds of Saigon

As an excavation of family history, Y Vân: The Lost Sounds of Saigon is less fraught than Murthy’s film but no less personal. Described as “the Quincy Jones of Sài Gòn,” Y Vân was a prolific songwriter in prewar Vietnam; his best known works pay tribute to a mother’s love and the South’s vibrant capital. After the war, many of his songs were banned and he fell into relative obscurity; the master recordings of his performances largely disappeared, leaving behind only scratchy records and sheet music. Fifty years later, his granddaughter Khoa Hà seeks to recover high-fidelity tapes and vinyl and resurrect his legacy. As she chases down leads from Hà Nội to Sài Gòn, her quest becomes both detective story and travelogue.

Hà, who worked as a designer and art director, too often leans on slick visuals and trope-filled narration in this first film. (It was co-directed alongside Victor Velle.) More welcome are the animated re-enactments and scrapbooks that bring to life a prewar Vietnam held only in the memories of a gradually dwindling generation. And of course, the soundtrack is excellent, boasting many of Y Vân’s compositions and contemporaneous covers of Western pop hits2; I’m patiently waiting for a record label to issue a box set of those remasters!

The Documentary branch of the Academy is pretty gatekeepy. They tend to shun films with lots of talking head interviews or entirely built on archival material, especially when it comes to making the final nominations, and they certainly don’t like any of the celeb-driven projects that are more widely viewed.