Comings and Goings At the Movies, Jan. 19

On Ava DuVernay’s Origin and Other Unconventional Adaptations. Plus: To Save and Project & The Breaking Ice

I meant to get this out sooner, but a combination of work, the cold weather, and other commitments kept me from writing! Here are a couple reviews for movies out in theaters this weekend, a writeup of a festival that spotlights film preservation, and some words on what I’m calling narrativized non-fiction adaptations.

And my year-end lists will be coming soon™. I promise.

Origin

Opened January 19 in limited release and will likely expand in the coming weeks.

If one were trying to adapt a non-fiction book that doesn’t have any kind of traditional story into a movie, a documentary would be the most obvious route. Talking heads, archival footage, you know the drill. Roger Ross Williams took this approach with Stamped From the Beginning, which is a solid documentary adaptation of Ibram X. Kendi’s history of racist ideas in America. But Ava DuVernay, the director best known for Selma and When They See Us, has taken a formally radical approach to convert a book of ideas into something inherently cinematic. Strictly speaking, Origin is not the movie version of Isabel Wilkerson's award-winning Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents. It’s the story about its author, researching and writing this book while grappling with grief on a personal and national level.

Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor brilliantly portrays the Pulitzer-winning author, allowing us insight into the woman behind the words. We get to know Isabel and her world. She gives lectures and attends publishing galas. She cares for her ailing mother (Emily Yancy) with the support of her loving husband (Jon Bernthal). It’s a pretty good life for a writer, but, like anyone else, she’s affected by what happens outside her immediate sphere. The murder of Trayvon Martin shocks the nation, and her editor at the Times wants her to write a column about it. But she demurs. In the wake of that tragedy, she asks questions about the bigger picture: “Why does a Latino guy deputize himself to stalk a Black kid so he can ‘protect’ a mostly white community? What is that [called]?” Isabel is someone who prefers to write about the answers to such questions. During a conversation with that editor, we see the gears turn in her head:

We call everything racism. What does it mean anymore? …Murders of Black people by police. We call that racism. Corporations say Black people can’t wear the natural hair growing from our heads in the workplace. We call that racism. Everything’s the same? … Racism, as our primary language to understand everything, seems insufficient.

There’s got to be a better way to describe this type of oppression. Inspiration springs from unlikely sources. The neo-Nazi march in Charlottesville gets her thinking about how Hitler’s regime subjugated Jews at the same time that African Americans were terrorized by Jim Crow laws. Reading a biography about an Indian jurist who was part of the Dalit (untouchable) class has her considering how social stratification can happen within racial lines. It’s the term of India’s hierarchical system that gives her the exact word she was looking for: caste. There’s a book in there somewhere. She embarks on research trips in Berlin, Delhi, and Mississippi: visiting landmarks and museums, interviewing people who studied the history and the people who were involved in it.

In DuVernay’s hands, what could have been a didactic lecture is instead a riveting tale that educates while it entertains, thanks to a few tricks. There's a lot of narrated flashbacks, which essentially function as documentary-style re-enactments, but with higher production value and shot with a bracing immediacy. There's also high-minded discussions between Wilkerson and fellow writers and academics, which cushions the “big talk” with realism simply because these people actually do speak like that. When the language needs to be more relatable, there's conversations between Wilkerson and her cousin Marion (Niecy Nash-Betts). And, at the end, when we get the Cliffs Notes of Caste, it only feels mildly perfunctory because it happens while we watch Isabel write the book itself. That’s not to say that the film is without its false notes. There’s a nearly unwatchable scene with Nick Offerman as a MAGA-hat wearing plumber, and sometimes the dialogue feels a bit too much like listening to NPR. But I’m largely impressed by the ingeniousness of this script.

If Origin were only about Isabel’s journey in researching and writing this book, it would have been a pretty solid movie. What brings it into the realm of greatness is how it’s also about Isabel having to work through grief while also working through her ideas. She suffers through the deaths of two loved ones in quick succession, and it’s in the details of moving on after a loved one’s death that Ellis-Taylor finds her character’s emotional depths. In a way, this is a straitlaced version of American Fiction, blending a story about society with a story about a family.

Although this movie’s tone is appropriately heavy, given the subject matter, it’s not all gloom. Isabel’s family tragedies are balanced with scenes of domestic happiness. A charming meet-cute, a comforting cookout: moments like these round out the film’s characterization of its protagonist. And the script emphasizes that Wilkerson’s book is not just a study of hatred propagated by the caste system, but a study of resistance against it. The German who refuses to salute Hitler, the anthropologists who embed themselves to document the horrors of the Jim Crow south, the Dalit scholar who rose up and helped draft India’s constitution: they’re all inspiring stories. But the film also shows that the simplest form of resistance against hate is love. Love between a mother and her daughter, love between a Black woman and her white husband; love that helps us get through and helps us break free. The final title card in Origin quotes the book’s dedication, and it’s that one sentence that ties together a book of ideas to a personal story about grief and loss. In telling the story about how the book was made, the film winds up telling the most basic, most beautiful story of all: a love story.

(I highly recommend reading Richard Brody’s review in The New Yorker, who is obviously much better at this writing thing than I am. And Robert Danels, writing for RogerEbert.com, gets into the specifics of how the filmmaking craft has an emotional impact.)

On Narrativized Adaptations

It’s pretty common to make a good movie out of a non-fiction book. This year saw Oppenheimer and Killers of the Flower Moon, both of which are great films. But unlike Origin, the books that those films were based on have a discernible narrative: the story of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the story about the murders of the Osage in the 1920s. Beginning, middle, end. That’s not to say that writing the scripts was a straightforward process, but there was a recognizable story to start from. With a film like Origin, it would be more accurate to say that Isabel Wilkerson’s book was the inspiration for Ava DuVernay to create a story, rather than an adaptation, since there isn’t a traditional story to work with. I’m not sure exactly what to call it, but “narrativized adaptation” seems closest to what I’m getting at here. The screenwriters for these movies have to conjure up a narrative that doesn't exist in the source material. Although this type of movie is rare, they certainly showcase a screenwriter’s ingenuity.

Anders Malm’s environmentalist manifesto How To Blow Up a Pipeline was transformed into a heist thriller which was released in the spring of 2023. A book that calls for the climate movement to employ violence as a legitimate tactic is not the most obvious candidate for a movie adaptation. But director Daniel Goldhaber and his collaborators successfully turned it into a gritty thriller without sacrificing its ideas. I watched it last week and thought it was terrific. A well crafted movie that's fun to watch with an incendiary message: we love to see it! It may surprise you to learn that Mean Girls was based on a self-help book titled Queen Bees and Wannabes: Helping Your Daughter Survive Cliques, Gossip, Boyfriends, and Other Realities of Adolescence. And He's Just Not That Into You was originally a self-help book as well. I can’t think of other examples at the moment, but I know that others exist. (If I were getting paid to write I’d certainly do some digging, and also read the plotless books that were transformed in the screenwriting process. But I write this newsletter in my free time 😅)

The Breaking Ice

Opened January 19 in New York at the IFC Center and expands to LA next weekend.

Yanji, a Chinese city near the North Korean border, provides a snowswept backdrop for the three lonely people who befriend each other in this subtle, understated mood piece directed by Sinagporean filmmaker Anthony Chen. With the inquisitive perspective of an outsider, he captures a generation's disillusionment. Yanji is certainly an interesting place: the signage is in both Chinese and Korean, and it's not uncommon for people to switch between the two languages in casual conversation. (Nearly half the population has Korean ancestry.) This blurring of boundaries parallels the characters, who are on the border between youth and adulthood. This place they find themselves in, whether a city or a stage in life, is just a waystation on their paths toward self-discovery.

The story kicks off when Haofeng (Liu Haoran, a big star in mainland China for the Detective Chinatown series) visits Yanji for a wedding. While waiting to catch a rare flight back to Shanghai, he befriends a melancholy tour guide (Zhou Dongyu) and a quiet restaurant cook (Qu Chuxiao). The coldblooded trio, two guys and a gal, thaw in each other's presence. They spend the subsequent days aimlessly wandering through a city that none of them call home, hanging out at bookshops and nightclubs and frozen rivers, with a lot of soju consumed in between. Shuffling through what should be the prime of their lives, there isn't much in the way of wacky hijinks; they're too depressed to get excited.

One would think that a love triangle would emerge, and it sort of does, but there's never any tension in the dynamic between these three. Chen, who has cited the French New Wave as a large influence on this movie, is more interested in the characters’ ennui. The Breaking Ice is most successful when it's exploring this, and exposition is given by suggestion. By the end, when our drifters part ways, they've all been changed by this brief encounter with each other, even if they'd never express that.

Out of the Vaults

Eighty percent of silent films are considered lost, which is an unfathomable number to comprehend. The MoMA's annual To Save and Project festival highlights the efforts undertaken across the globe to preserve movies that are at risk of disappearing, and showcase the victories in recovering films long thought to be gone forever. (This isn’t limited to silent films: censorship, copyright, and negligence can bury any movie.) Most of the films in the program are best viewed from a more scholarly perspective — it's not like they’re all forgotten masterpieces — but it's always fascinating to see their place in film history.

Last weekend, I saw Man, Woman, and Sin, a romantic drama that has basically been unseen since it was released in 1927. It's a weird story. Although it was a hit, at the time the studios didn’t really care to preserve their movies, and MGM lost track of the film prints. In the 1970s, a movement to preserve films began, and this particular title was re-discovered in a warehouse and given to the Eastman Museum for preservation. But it couldn't be released or screened: the rights to the movie at that point had been sold to either Warner Bros. or Universal and no one could definitely determine who owned it, and no one at either company expended much effort to resolve the issue. The movie remained mired in copyright limbo until it fell into the public domain in 2023. So, finally, the Eastman Museum was able to digitally restore the film, and a year later, the MoMA was able to screen it!

I'd love to say that the film — never seen in nearly a hundred years! — was stunning, but it was rather forgettable. The story concerns a newspaper reporter who grew up poor, falls in love with a co-worker who is the mistress of the paper's owner, and melodrama ensues. The picture's significance lies in it being a rare screen role for Jeanne Eagels, who was a Broadway superstar, as well as some location shooting in Washington DC, back when it really was a swamp town. It was one of those cases where hearing about the movie was far more interesting than the actual movie.

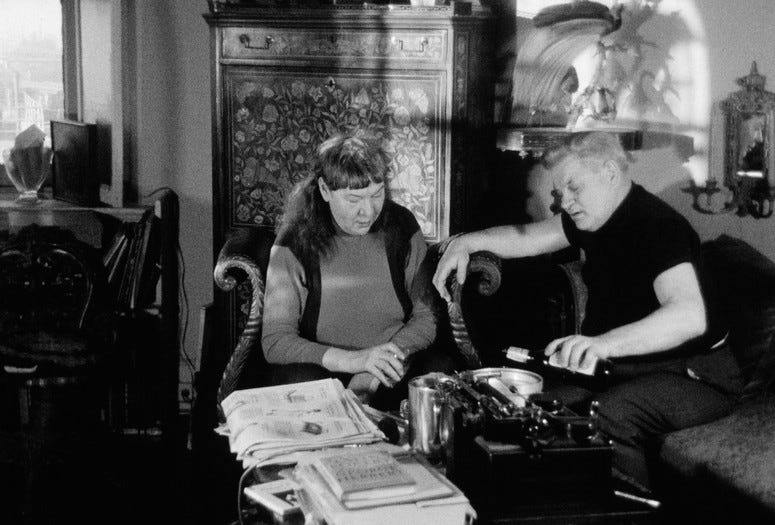

I felt the same way about Bitch, an Andy Warhol movie that had literally never been shown until last weekend. Warhol’s films were usually more about the concept: one of his most infamous movies is an eight-hour long static shot of the Empire State Building. With Bitch, a camera is trained on the sitting room of a Brooklyn Heights apartment. It’s mostly unwatchable thanks to muffled dialogue, so I tried to follow the body language and the tenor of conversation to track the relationships between the six people who appear on screen. A married couple are at the center of the party, but the husband's boyfriend shows up, and the wife starts making out with another guy. Edie Sedgwick shows up too, in her first on-camera appearance.

The old couple in Bitch was the inspiration for the characters in Edward Albee's famous play, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, which Mike Nichols turned into a movie. The MoMA put that movie, projected from a pristine 35mm print, on a double-bill with Bitch, and the chance to see Woolf on a big screen was why I showed up. It was one of those classics that I had just never seen until now, and the movie version is perhaps one of the greatest stage to screen transfers ever made. The repartee between Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor had me alternating between a dropped jaw and a wide grin. Sure, I could have watched this at home at any time, but sometimes it takes events like these for me to actually see it.

Later today, I’ll be seeing two newly restored silent films that were each led by Anna May Wong and Sessue Hayakawa, the biggest (and the only) Asian American movie stars of the silent era. Hopefully I’ll have more positive things to write about those movies! You can check out the rest of the lineup here; and not all of the movies are meant to be viewed in a more academic context. I’ve got my eye on a screening of a Hong Kong action movie by Tsui Hark that is described as “an incendiary jeremiad against colonial occupation and political corruption.”

Thank you for bringing back my favorite feature! :D